On Saturday, October 11, I visited the Sidney Larson Gallery at Columbia College to view the current exhibition, “Everything at the Same Time,” featuring sprawling, luminous works by local artist Caleb Crites. Crites spoke to a small group about the stories of these pieces, which will be on display through Wednesday, Oct. 22. For more information about art galleries and opportunities in Columbia, please visit DBRL’s Local Arts Guide.

“We are here to help each other get through this thing, whatever it is.”

By the time Caleb Crites welcomes his visitors with this Kurt Vonnegut quote, I have already made my way around the room. The Sidney Larson Gallery is an intimate space which bends easily around the eyes; it takes only a few steps to travel between paintings, and a well-placed gaze to hold them all in view at once. I have done both — zoomed in and zoomed out — so it is a relief to be addressed this way, to be brought back into the fold.

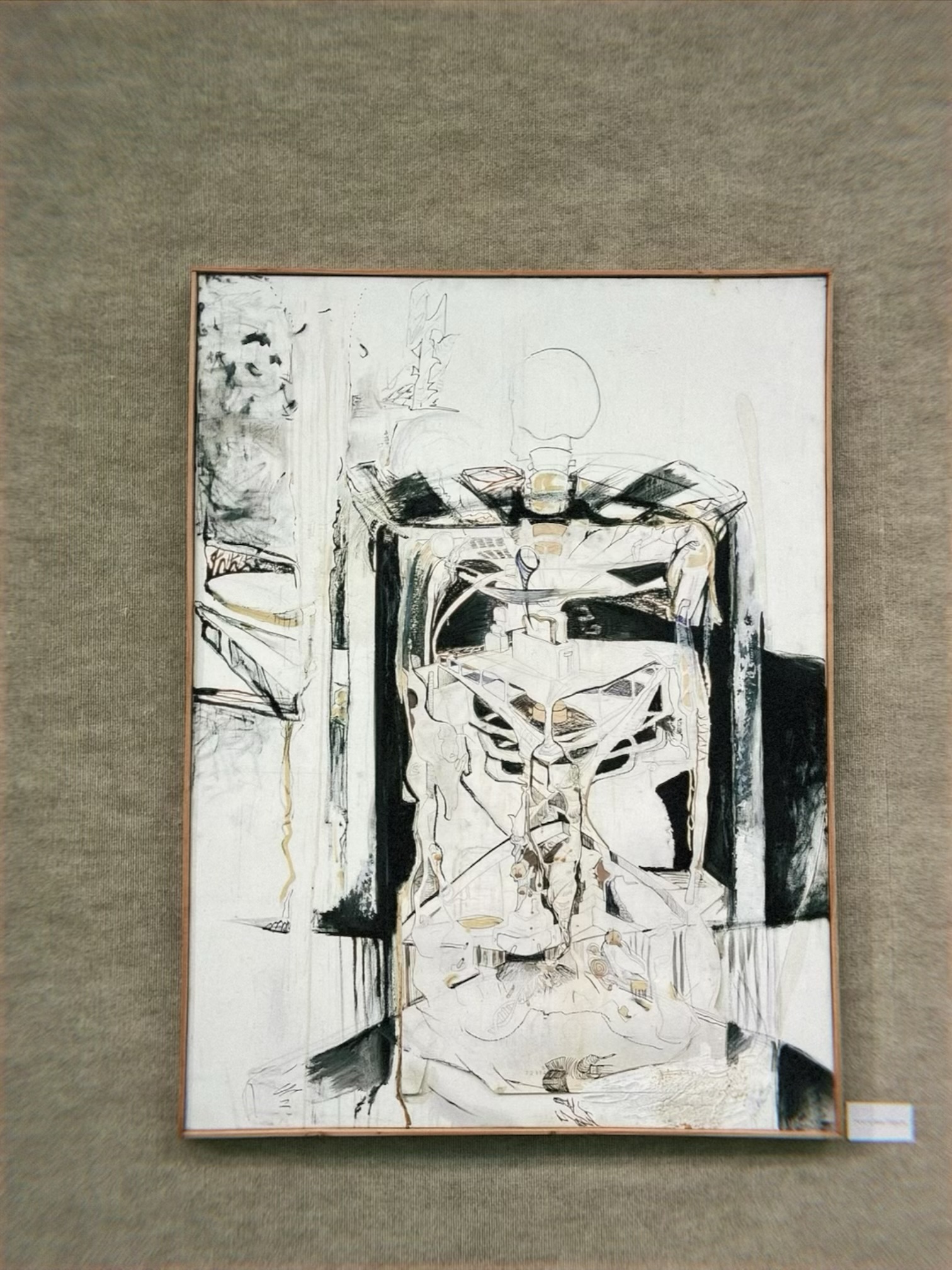

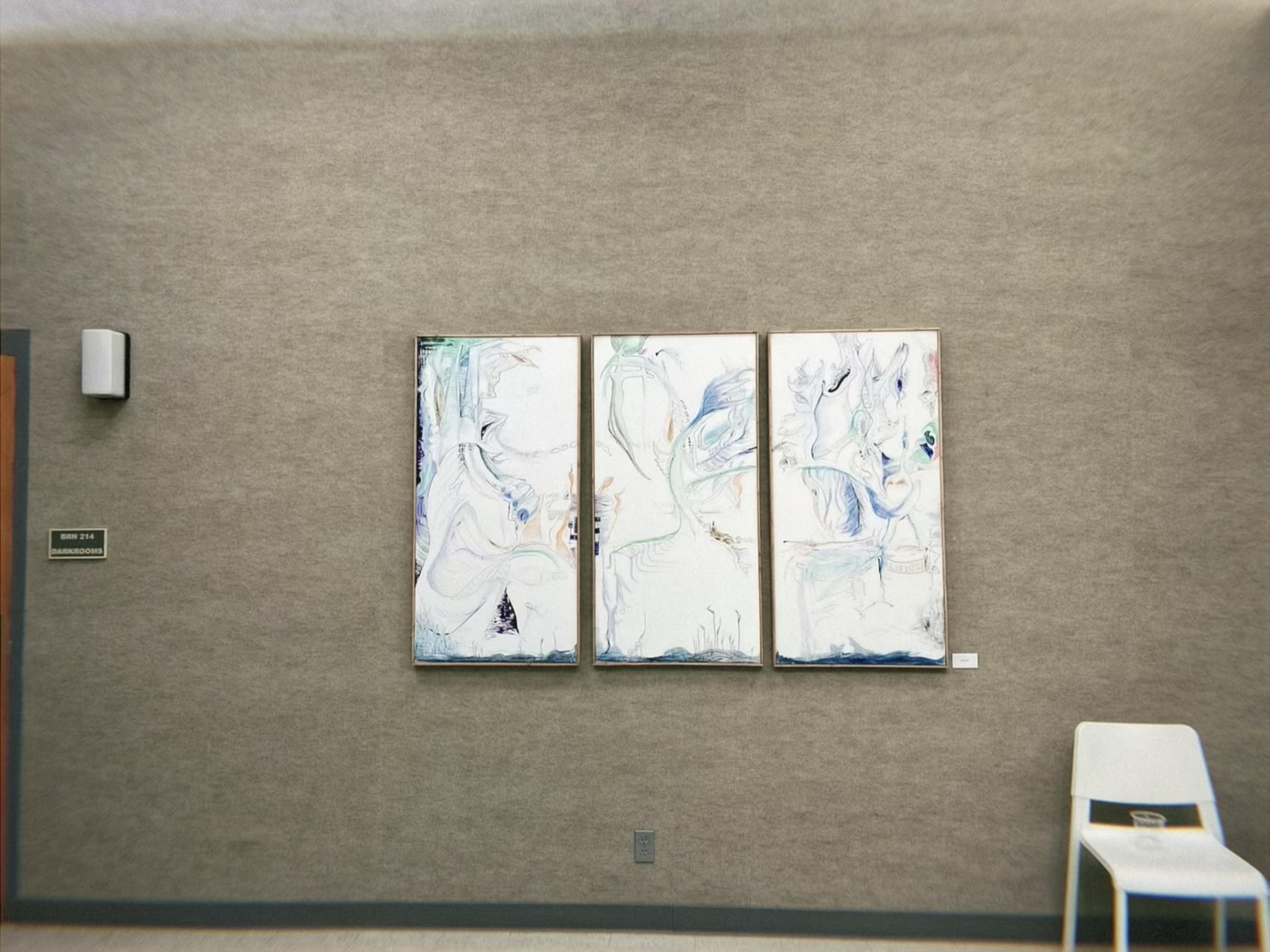

“Everything at the Same Time” is a world (or, various dimensions of an indeterminate number of worlds) rendered in 14 paintings. I am disoriented by “Anticline,” as if falling into a snow globe, until my friend says it looks like a map — then I begin to follow the paths, circle the lakes, stroll at my eyes’ leisure. A black and white piece draws my attention, colored only by what looks like coffee stains, some milkier than others. Hourglass, I think, tracing the curves and drips, then my friend takes a step back and says: Skeleton. (Of course — there is the ribcage, the vertebrae, coffee for spinal fluid.)

“Many artists are opposed to or uncomfortable about working free-hand, committing their own lines to the page,” Olivia Laing writes in “The Lonely City.” “Sometimes this is about wanting to avoid determinism, à la Duchamp, who said about one randomized work: ‘The intention consisted above all in forgetting the hand.’”

In Crites’ paintings, the hand is everywhere. Each line seems alive with a human whimsy: Here a wrist flicks, a finger dabs, a glitter pen lets loose. Images unfold like pages of a journal, and in some places real words appear — floating fragments of lyrics or jokes, precious enough for the canvas even in their ghostly forms. “Sometimes I have an idea for a song and it might be one or two lines, and I write it down on whatever’s closest to me,” Crites says. “If it happens while I’m painting, it’s going in the painting.”

My own writing is a disfluent process slowed by constant decisions about what doesn’t belong on the page; it can feel like the work cancels itself out (“like balancing two sides of an equation — occasionally quite satisfying, but essentially a hard and passing rain,” as Maggie Nelson writes in “Bluets.”) So I listen in slight disbelief as Crites describes his practice, how discoloration on the canvas or a stray cat hair can open portals to explore, how a spill becomes a question: Where does this color want to go? “I start painting by planting little seeds and watching them grow,” he says. (This is creation without equations; not the rain but the seed.)

Sometimes more specific wonderings guide the work, like in the brilliant “Prism Inside a Cube of Mirrors.” This is Crites’ exploration of a world he cannot see, his answer to the questions: What if one’s lifeline appeared as a shard of light suspended within a transparent Rubik’s cube? How would this light travel from one point to another? “It’s really just light everywhere,” Crites says. “Infinite possibilities.” (I wish I had taken a picture of “Prism.” Mostly I remember galactic, intoxicating purples and reds, and my friend pointing to a glowing wedge: “Cheese.”)

When we’re through with the paintings there is one more piece to share — a song, the show’s namesake, performed by Crites on guitar. Every string sings, the room swells. The song, like much of Crites’ work, is cocreated with an element of chance: “One day I was on her porch swing, my mom’s house, and the creak of the chain sounded like a couple words,” he says. “I ran and grabbed the guitar, and then I just started singing.” (Think “Big Sur,” Jack Keruoac hearing poetry in ocean waves.)

“Everything at the Same Time” is a lesson in sensitivity and permeability, a call to let the world move through you. And yet the call is not simply to feel, but to distill this energy and offer it back up. The infinitely mirrored lifeline in the Rubik’s cube still wants to go somewhere — the light may appear to project randomly, but a moral imperative is at work: “There’s a way of traveling. It’s all overlapped…but maybe you can get to a better place if you think good thoughts and focus on doing the right thing,” Crites says.

A song for the porch swing, a story for the coffee stain, infinite paths for a lifeline. Crites reminds us to let moments leave their mark, to notice the random gifts of this world and respond:

“Exploration pays off. Even when you don’t know where you’re going and you don’t think you’re going anywhere, then you’ve just got to keep going. I think you’ll get somewhere. I think I have.”

-Karena