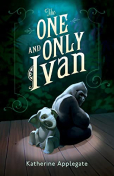

The first time I read “The One and Only Ivan” it upset me. I grew up spending many, many hours watching Ivan the gorilla at the B&I shopping center in Tacoma, Washington. My grandfather would take me on errands with him, then get himself a coffee and each of us a donut, so we could sit with Ivan for a while before going home. I read all the articles pasted on the walls, saw all the photos, and mostly just enjoyed my time with Ivan. Even as a small child, I knew he didn’t belong there.

The first time I read “The One and Only Ivan” it upset me. I grew up spending many, many hours watching Ivan the gorilla at the B&I shopping center in Tacoma, Washington. My grandfather would take me on errands with him, then get himself a coffee and each of us a donut, so we could sit with Ivan for a while before going home. I read all the articles pasted on the walls, saw all the photos, and mostly just enjoyed my time with Ivan. Even as a small child, I knew he didn’t belong there.

Ivan was such a character. Some days he just sat around doing nothing. Other days he threw me balls, wiped boogers on the glass, made faces and played. The days he was quiet I was incredibly sad for him, but the days he was active are some of my happiest memories. He placed his hand on the other side of the glass from mine many, many times. I like to think he recognized us, but that may be a pipe dream. As an adult, I have a sense of guilt about enjoying his captivity as much as I did. I wasn’t the one that captured him. I never teased him, and I always loved him, but I still sat there and enjoyed seeing him. Was that wrong? Probably, but as a child, even though I knew better, my NOT watching him would not have freed him. It’s an eternal dilemma.

My childhood created a lifetime fascination with gorillas. I recently purchased prints of a few of Ivan’s paintings. Upon their delivery, I fell down a rabbit hole of research. This is not the first time I’ve fallen down this particular Ivan deep dive, but it did lead me to reread this book. Having a bit of distance made me more appreciative.

This book upset me the first time I read it because it painted Ivan in abject misery. I didn’t want that to tarnish my happy memories of him. But that’s selfish. How could he have been happy there? I was complicit in his captivity, and although I could have done nothing about it, I can’t be pleased with my nostalgia. Author Katherine Applegate first made me feel guilty, then made me think. That made me mad at first, but isn’t that what good writing is supposed to do? Especially with literature aimed at youth?

Applegate wasn’t really telling my Ivan’s story — she was telling the stories of all captured wild creatures in a way children can understand who did not get to see Ivan (or others) firsthand. The Irwins, Ivan’s original owners, were more well-meaning than Mack, the owner in this book. Earl Irwin actually purchased Ivan and his sister because they would have been euthanized had he not. I don’t mean to say they weren’t wrong in eventually keeping Ivan in that way, but they weren’t as cruel and heartless as Mack. Their intentions were good. Larry Johnston grew up with him and spent much of his life with Ivan in it. He was raised to believe and feel a certain way about Ivan, and don’t we all struggle with our heritage? Larry was a child when Ivan entered his life. What is a child to do? Would any kid turn down the notion of a gorilla as a playmate?

Ivan spent 27 years at the B&I shopping center in a 14′ x 14′ concrete enclosure, a yard area, and a trailer with toys and handlers, but in 1994 he was moved to the Woodland Park Zoo. He was eventually placed at Zoo Atlanta, and while my heart hopes he was happier there, he was never really a gorilla because of his decades in the Johnston’s “care.” He died at 50, under anesthesia for a check-up. As sad as this has always made me, Applegate allowed me, with this little book, to think he may have died with some happiness having stepped on real grass, felt the wind in his face, and seeing others of his kind in the open air. I still hope.

Three words that describe this book: Eye-opening, sad, hopeful

You might want to pick this book up if: You are trying to teach children about our place in the world in relation to the animals with which we share it.

-Kandice

This reader review was submitted as part of Adult Summer Reading. We will continue to share reviews throughout the year.