Some months I approach reading as a challenge or a project, hoping to end up somewhere new; to have made sense of something previously unintelligible to me. But in January my readings and viewings were more about settling the mind than stretching it. I gravitated toward rhythmic, reflective works that felt a bit like listening to a friend (warm, maybe a bit repetitive, with a feeling of goodwill at the core).

December was for journals! I loved spending time with the diaries of dear artists, considering their inner monologues and exploring my own. But journaling, done deeply, is not simply a matter of navel-gazing — any Thich Nhat Hanh book will tell you that the way you speak to your own heart informs your compassion towards others. That’s why “The Art of Communicating” begins not with strategies for interpersonal communication, but with mindfulness practices for the individual. When Hanh introduces the mantra “I am here for you,” he invites the reader to embrace and emanate the sentiment in all directions and dimensions, until devotion flows with ease.

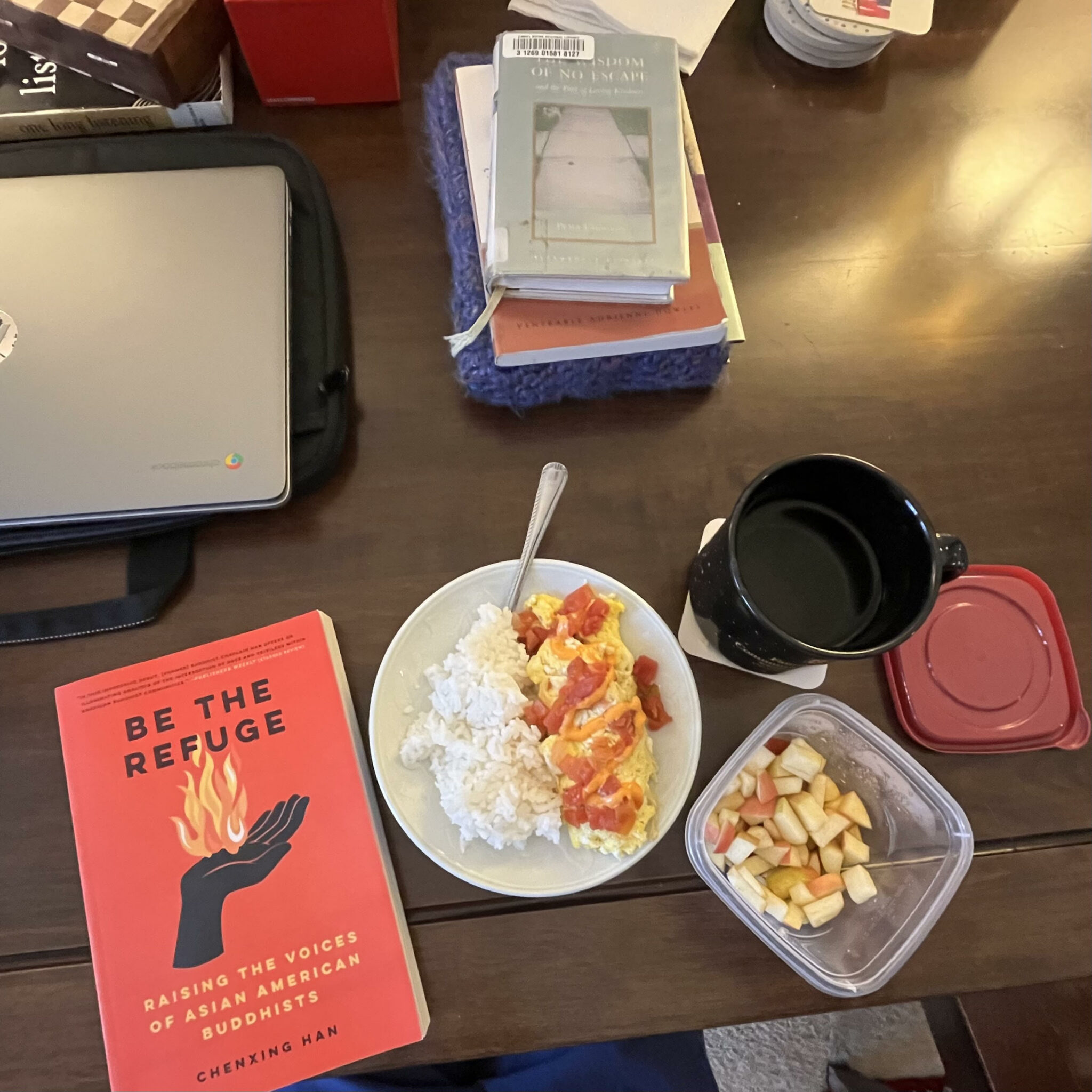

I read “The Art of Communicating” concurrently with “The Wisdom of No Escape” by Pema Chödrön, another beloved Buddhist writer and teacher. This book is a series of talks given by Chödrön in the spring of 1989. (You might find that the length of one talk is more or less compatible with the unhurried enjoyment of one meal + cup of tea.) I was fascinated by the discussion of tonglen meditation, which involves the visualization of darkness and pain on the in-breath and lightness and healing on the out-breath. “You will be surprised to find yourself more and more able to be there for others, even in what used to seem like impossible situations,” writes Chödrön in a blog post on this practice.

What does the spirit of tonglen (which translates roughly to “sending and taking” from Tibetan) look like in practice? I think it looks a bit like Aaron Lee, a young Buddhist writer and lymphoma patient, asking himself how he could be a refuge for others from a hospital bed: “In the hospital, I used my speech and actions as refuge for my family and caregivers — providing them with a space where they could feel calm, positive and helpful,” Lee wrote to the writer Chenxing Han shortly before his passing in 2017.

“Be the Refuge: Raising the Voices of Asian American Buddhists” is the jewel forged from Han’s friendship with Lee, along with years of in-depth interviews with a pan-ethnic, pan-Buddhist group of 89 young adults. No one else writes like Han — rigorous but not demanding, poetic yet grounded, always soulful and surprising. (Her second book is no exception.) I will be revisiting this luminous piece of scholarship/memoir/history for years to come.

If Aaron Lee shows us how compassion can arise from a hospital stay, Thich Nhat Hanh explores how it might look in a workday. In his book “Work: How to Find Joy and Meaning in Each Hour of the Day,” Hanh points out all the small opportunities for emotional renewal before, during and after work. A moment in the morning to name our gratitude for a fresh 24 hours, a deep breath at a stop light, a pause before picking up the phone to appreciate the human on the other end, whoever they may be.

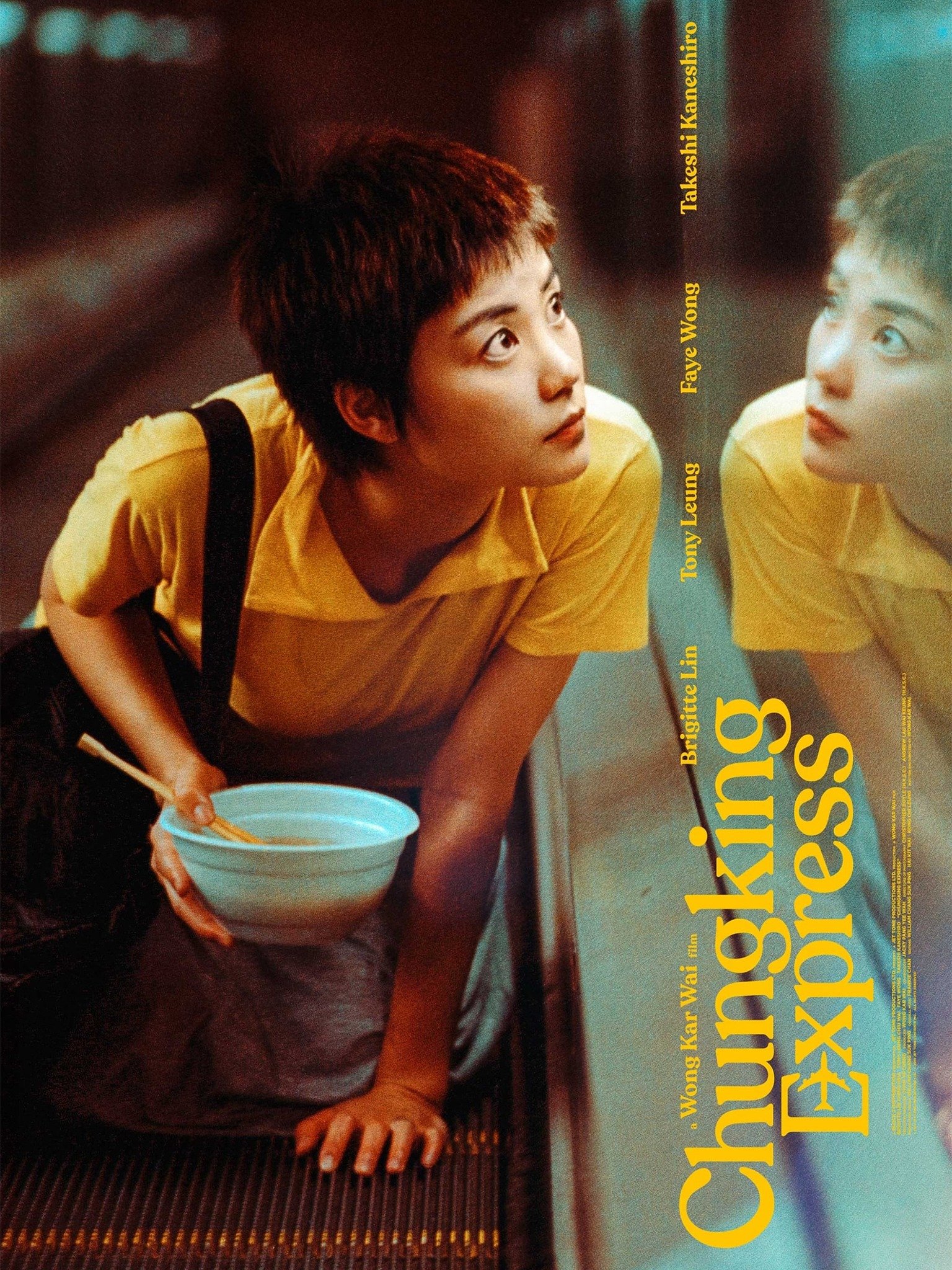

It was refreshing to consider Hanh’s guidance for nurturing presence and sincerity while working, but there was also something healing about the story of Faye — terrible worker and shining star of “Chungking Express.” In this winsome classic of Hong Kong cinema, a food store worker busies herself with blasting music, neglecting tasks and falling in love. Thich Nhat Hanh might raise an eyebrow at Faye’s tendency toward escapism and indulgence, but maybe he would appreciate the depth of her love; her devotion to the happiness of a near-stranger.

Wong-kar Wai made enough magic with “Chungking Express” to set a whole other movie in motion, “Fallen Angels” (freely available on Kanopy). It is the younger, stranger sibling of “Chungking Express,” bearing darker storylines originally written for the earlier release. Takeshi Kaneshiro’s performance as Ho Chi-mo, a mute ex-convict, is both the soul and the comic relief. We never hear Ho Chi-mo speak, but the narration of his inner monologue casts a soft glow over the world of “Fallen Angels” and all its lonely people:

“You rub elbows with a lot of people every day. Some strangers might become your friends or even confidants. So I never turn my back on a chance to rub elbows. Sometimes I rub till I bleed. No big deal.”

Thank you, library, for the comforting stories (on paper, on disc, online). / Thank you, Thich Nhat Hanh, for the fresh spring of your wisdom. (May you rest in peace.) / Thank you, Pema Chödrön, for your compassionate talks. / Thank you, Chenxing Han, for your radiant research and writing. / Thank you, Wong-kar Wai, for the beautiful and nostalgic scenes of Hong Kong. / (Thank you, for reading!)

-Karena